In Stephen Collins’ graphic novel, there is a noted divide between the familiar, ordered, and organised world of Here, and the chaotic and unknown nature of There. The Gigantic Beard that was Evil centres around one major, unavoidable and disruptive change: the growth of a gigantic beard on the modest and unassuming office-worker, Paul.

Looking back to some of the first questions posed by the ancient Greek philosophers, we can see a clear preoccupation with this concept of change; of things coming about which previously were not; of things over there, becoming part of our here. For example, this division is a key part of Aristotle’s cosmology, where the universe is divided into the superlunar realm (everything beyond the sphere containing the moon) and the sublunary realm (everything below the moon). Aristotle argued that everything in the superlunary realm was made of one pure celestial element, whereas everything on earth was composed of the four elements, and could change. This fed straight into theological (Christian) doctrine, whereby everything on earth was susceptible to decay and corruption, whereas the heavens were secured in perpetual perfection. Going further, the philosopher Heraclitus believed that change was everywhere. He is associated with the phrase panta rhei, which means (roughly): ‘everything changes’. Heraclitus uses the example of a stream: the water flows constantly, replacing the water that was previously there, so that ‘we may never step into the same river twice’. For these philosophers, change creates circumstances in which there is no reliability. In a similar sense, Collins uses the idea of ‘tidiness’ to represent the human aversion to change.

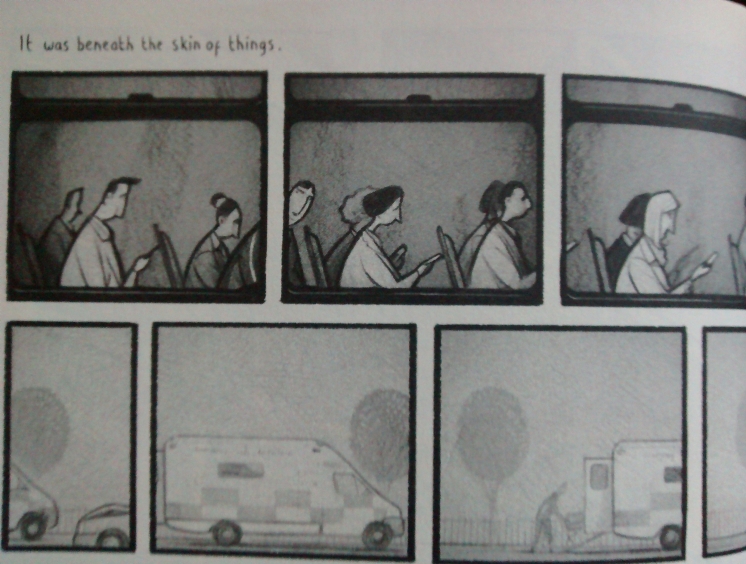

However, in The Gigantic Beard that was Evil, it turns out that change is a necessary component for the existence of value. In order to show this, Collins’ begins with introducing us to a world which has managed, somehow, to completely escape change: change is suppressed into non-existence. This leads Paul to question the meaning of his actions: ‘Did any of what he’d just said mean anything at all?’ he asks. This shows that order and repetition can make meaning redundant. In reality, the nature of time forces change upon all aspects of our lives, and even this dystopia created by Collins cannot escape it completely. Time finds a way ‘through the invisible gaps which connect one moment to the next’. For the inhabitants of here, time (and with it, change) is solely the concern of there. The nagging doubt described in the members of the public shows that ‘there’ is supposed to represent this notion of change, and therefore the concept of time.

Here, we can see change represented by the ultimate change: death. This inescapable consequence forces all those who witness it into acknowledging the existence of time. And this is where change begins to seep into Paul’s world.

So, what value does change hold for us?

There are two responses to this, which are both represented in The Gigantic Beard. First, we have Paul’s initial reaction: nausea. The lack of purpose to things in the world of the Here means that the initial sign of change, of disorder, which expresses itself in the form of his spontaneously growing beard, causes an internal dread. The beard becomes an exaggerated symbol for Time; its rapid growth emphasises the previous stagnation and suspended nature of existence within Here – with Here now representing an isolated present. This is reinforced by the fact that ‘here’ is a grounding word (an extension of the auxiliary verb ‘is’: to be here, is to be), whereas, ‘There’ distinguishes an uncertain other. In this way, ‘there’ also comes to represent the uncertainty of the future in a universe full of chaos.

Here, there is an assured reason and order to everything. However, ‘Sometimes […] Dave would wonder what it was his company actually did’. When he questions his colleagues, they can always provide some kind of answer, but these are empty and meaningless: ‘It’s insurance, I think’. The arbitrary and superfluous coming-into-existence of the ‘Gigantic Beard’ shows that there isn’t a reason to everything; there isn’t an essential ‘tidiness’ to the universe. This notion of a meaningless universe comes from the philosophical notion of Existentialism. The French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre wrote that it is because we are in fact free to make our own choices, and that there is no reason for us to act one way over another, that we experience what he terms ‘La Nausée’: Nausea.

And yet, Paul moves through his nausea, and it is this second response which brings in the positive aspects of time, and change: the idea that these things contribute to the value our lives hold. Paul’s beard comes to represent the true nature of life – its lack of order and cause – but with this disorder, we have the development of imperfection, which in turn generates uniqueness: ‘Within a year, most people could barely remember what they were once afraid of’. Indeed, when Paul is fully confronted by his gigantic beard, in a pivotal moment in the graphic novel, all he can say is: ‘It’s beautiful’. In this way, Collins shows that change is beautiful, and leaves the reader tranquil and at peace with their imperfections.

Love this graphic novel soooo much!!

LikeLike