Picking up Heat by Jean Wei was an instant delight: the illustrations within are so colourful and charming; you flick through the pages and see a usually unwelcomed visitor being taken in by a small and unassuming family, seamlessly falling in place and into the flow of everyday life with these people. Upon closer reading, however, we see a much deeper narrative centred on the importance of forgiveness.

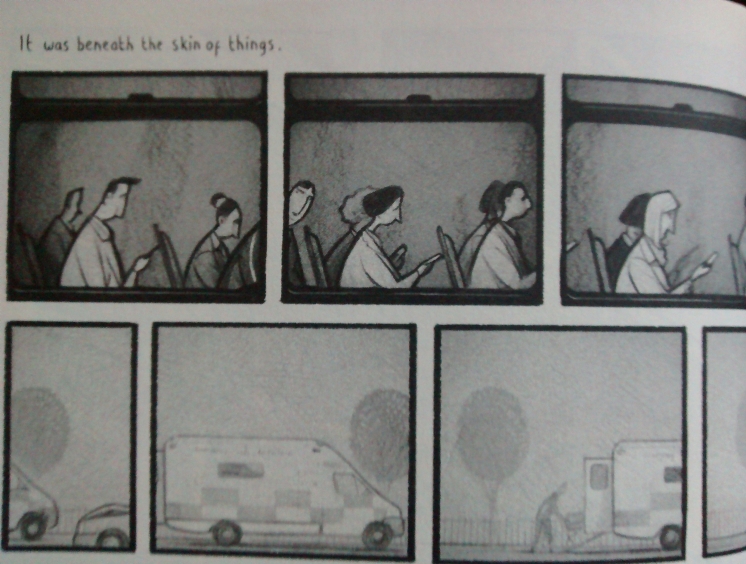

Heat follows a giant, naked fire demon through their transition into a quiet but hardworking farm-hand [1]. This quaint, rural farm is run by Auntie Anne and her Grand-Niece Katy, and for a good majority of the book, we bounce along quite nicely; watching the relationship between the trio grow and also witnessing the caring relationship between Anne and her love-interest Clara. Cute scenes unfold: we see our fire demon – who earns the name ‘Red’ for obvious reasons – is taught how to help out on the farm and around the house, witness the tender moments between Red and Katy, and smile at the child-like innocence of Red encountering everyday situations, as well as their quiet moments of solitude.

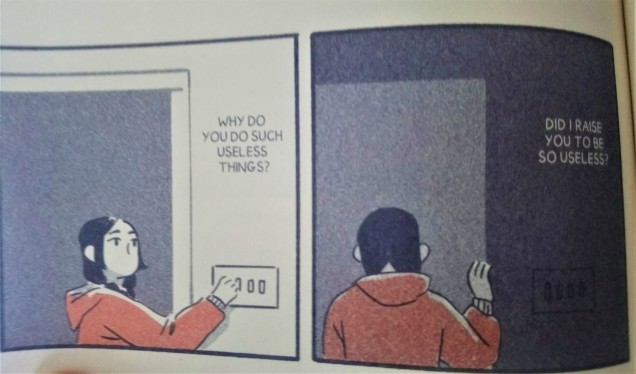

Then we see a relationship which is not so clear-cut, drawn into even sharper focus through the contrast with the kind and tender relationships prior to this. For there has been a falling out between Anne and her actual Grand-daughter, Maya. The two haven’t been seen together for years, and it is revealed that Maya had left the farm to start a small glass-making business with a partner. We are shown there is a clear divide between them, but the exact nature of this fall-out is only hinted at. It does, however, seem to be focussed on a dispute over Maya’s role within the family, on the consequence of her actions and the reasons behind them. Essentially, there appears to be a conflict surrounding purpose, and this has thrown Maya to question where she belongs.

On the one hand, Jean Wei draws a strong contrast between Anne’s relationship with Maya and her relationship with Red, whilst on the other, both Red and Maya appear to be going through similar identity struggles. Both are wondering about their utility; Maya wondering ‘Was I useful?’ and Red being criticised by the narrator, who we can even read as Red’s own internal dialogue: “What are you, Demon? Do your job, Demon. Useless Demon… What are you”.

In the end, through Red, Anne is allowed to enact the forgiveness she has never been able to give to Maya – perhaps through stubbornness, anger, or hurt: “[…] you’re more than the help you’ve given me here […] You don’t need to deserve to exist. You don’t need to prove anything to me. I’d just like to spend more time with you”. Here, the word ‘deserve’ is key; to deserve something implies that you have earned it somehow, through your actions and behaviour. We could see this as relating to an imagined individual purpose. But Anne realises that this is tangential to existence; that, as the Existentialist philosopher Jean Paul Sartre wrote, ‘Existence precedes essence’ [2]. This means that we exist before we can determine our own purpose and there is no such thing as a ‘reason for existence’ already embedded within us.

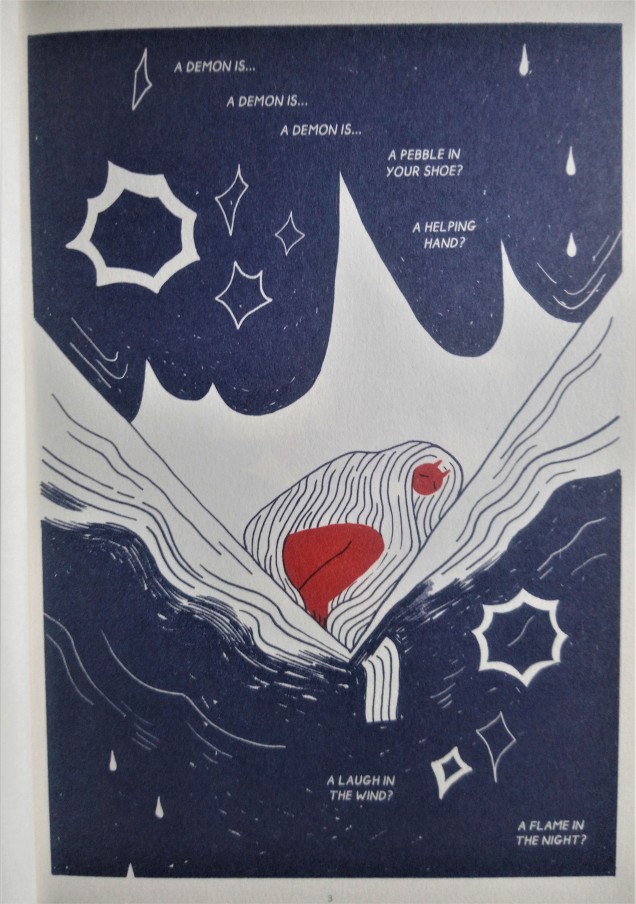

Yet, Red goes against this in the very beginning, where our narrator taunts ‘But, warm one, what are you? What more can you be? What more, but to bring fire to light!’. For, usually, heat is something that is necessary i.e. as a casual response to fire. Unlike the concept of heat, however, we humans do not have such clearly defined reasons for existence; there is no rule telling one person that they are made to tend the fields and another that they are to shape and create magnificent works of art from the dangerous and sharp-edged material of glass.

Red, the embodiment of heat in this story, goes against this predetermination and instead carves out their own path. This is what leads Anne to realise that it is simply being human that is worthy of consideration and acceptance; our human freedom, and with it, our mistakes and our triumphs, unites us. This should allow us to be a little more forgiving of others, and I hope it helps Anne and Maya forgive each other too, finally.

—-

[1] Wei, Jean, Heat (Peow Studio, 2018)

[2] Crowell, Steven, “Existentialism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/existentialism/>.