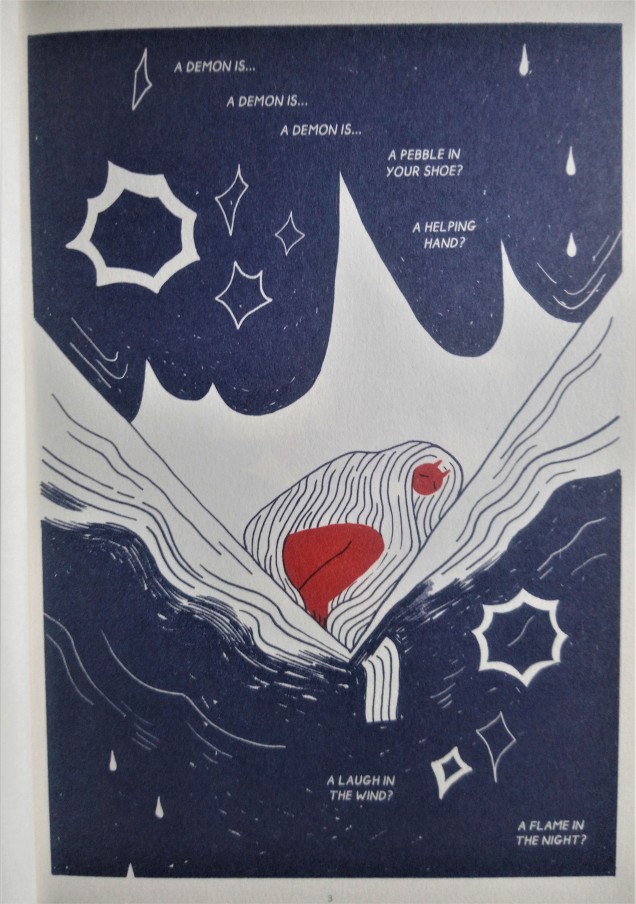

Reading Persepolis, especially as someone born and raised in the West, is a real eye-opener. Our self-aware narrator Marjane knows the reality of this Western ignorance all too well, and in the introduction to Persepolis, she notes simply: “… this old and great civilization [Iran] has been discussed mostly in connection with fundamentalism, fanaticism, and terrorism… I know that this image is far from the truth”. This large collection of short autobiographical comics—in essence, a comic version of a short story collection—is an honest and open attempt to capture the true images of Iran; a response to the dismissal of its history and the people who experienced it. But most importantly it reads like an affirmation of selfhood and the duality involved in this: at once seeing yourself as an individual and yet also as one part of a much wider group.

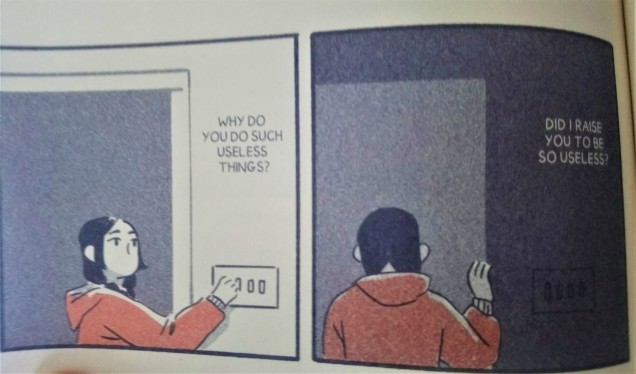

Literally divided into two parts, part one covers Marjane’s experiences growing up as a child in Iran; with the bombings, hostile surveillance and oppression brought about by the regime. She captures the innocence of a child’s perspective through humorous and brusque scenes, which subsequently act also to lull the reader into a false sense of familiarity, only to be left in the lurch when they are just as swiftly confronted by violence and brutality. Starting the book with these recollections allows the reader to piggy-back along with Marjane’s own revelations and discoveries; as she grows up and learns more about her own country, she shares this knowledge and the realities it entails.

The second part is about Marjane’s time away from Iran, and then the eventual return, as an older and conflicted young woman. It is in this part that Persepolis considers the importance of these earlier memories and their relation to Marjane’s personal identity. The philosopher John Locke argued that personal identity is nothing more than our memories; our memories are how we can say we are the same person we were previously. In Persepolis, Marjane sets out her memories in an objective form through an act of bearing witness. However, she is not just witnessing the horrors of war and oppression, but also to the individuals forgotten by the all-encompassing nature of these phrases. There is a definite difficulty faced in trying to readjust to the Iranian lifestyle, having gained more awareness and exposure to the rest of the world: the regimes are now even more intolerable, the streets and her friends only serving to remind her of the disparity between her roots and her more recent experiences away from home.

Persepolis contains so many stories, each so personal it feels as if these are the tales of a friend: relatable hurdles of youth are thrown against the extreme backdrop of war and continual persecution. Told through ink, the simplicity and generally small scale of the panels adds to their relatability; Marjane takes us to parties, on dates, to school and through university. These emphatic scenarios make sudden violent turns even more shocking and distressing. It is well worth bearing witness to these tales and the history of all those whose lives are brought to life through Marjane’s memories.

—

Persepolis (Vintage: London, 2008)