If you have read any of Murakami’s short stories, you will know how their brevity really emphasises the search for meaning in his narratives. I have discussed the ambiguities of these meanings previously, but there is also a plurality of meaning which is being highlighted by the imagery used. This imagery is so strange and unique, that we cannot help but imagine some grand meaning behind it – why are her ears so beautiful and magical, why is her sister in an endless slumber, and why on earth are fish falling from the sky? His conversational tone invites us to seek out these connections, and I feel as though, as a reader, I am being teased with the answer to some great secret being dangled directly on the page.

Michael Dachstein’s ‘Time Traveler’ via Google images

Nowhere is this more obvious than in Murakami’s short stories, where large casts and sequences of events are no longer diluting the metaphors and symbolism present. Instead, we are forced to confront the meaning directly. In ‘Nausea 1976’, particularly, we are presented with quite a simple story – readers of his larger novels will be familiar with untangling more complex narratives, jumping all over the place both spatially and temporally – in which our narrator is talking to his friend who tells him of a time when he has a strange case of vomiting for ten consecutive days [1]. Yet, during this period he experiences no other symptoms or discomfort but simply finds himself unable to keep meals down, and every day he receives a strange phone call from an unknown caller, who would simply say his name and then hang up.

Listening to this story, along with our narrator – who turns out to be Mr Murakami himself – I found myself using every detail given as a clue to help form some kind of connection between the two. There were clues as to why it started, but less as to why it ended when it did, and there were clues as to why there were phone calls, but less as to why there was nausea. Is it because of his lack of romantic emotion or his continual betrayal of friends? Is he being punished by them, or by some other force? Of course, there was no definitive resolution as the end.

However, we are given an insight into Murakami’s phenomenological attitude toward these kinds of metaphors and symbolism. Phenomenology, in philosophy, considers the unique experiences that having a consciousness necessitates [2]. In other words, it considers how our consciousnesses make us see the world in different ways, due to varying intentional states of the perceiver. For Murakami, the same holds for stories. At the end of his bout of nausea, the mysterious caller says one additional thing to Murakami’s friend: ‘Do you know who I am?’ (p. 195). ‘Do you know who I am?’ – the ‘know’ informs us that the answer is something which needs to be sought out, it needs to be considered, it is an ‘intentional state’ which phenomenology claims can lead to a change in meaning.

Additionally, our mysterious caller invites the reader into a privileged dialogue with one of Murakami’s metaphors, asking us to really consider it. The friend tries this, in as logical a manner as he can manage given the strangeness of the situation: ‘I suppose it could have been someone from my childhood, or someone I had barely spoken to […]’ (p. 195). All of his suggestions revolve around his own experiences and memories (‘from my childhood […]’), prompted by the questions appeal to what he may ‘know’; an appeal to his own consciousness (for how can anyone really ‘know’ what is experienced by another…?). And yet, this is inevitable. Of course, any metaphorical meaning we do consider is likely to be self-projected:

“So, what you’re telling me, Mr Murakami, is that my own

guilt feelings – feelings of which I myself was unaware – could

have taken on the form of nausea or made me hear things

that were not there?”

“No, I’m not saying that,” I corrected him. “You are.”

(p. 195)

This goes for all of Murakami’s work, he is offering up his metaphors to the reader; allowing them to find their own meaning in his stories: ‘[…] I’m not saying that,” I corrected him. “You are.”‘ He surrenders authorial intention, and with it places the responsibility for meaning in the hands of the reader: ‘Anyhow, it’s just a theory. I can give you hundreds of those.’ (p. 196). Or, as Irish poet Louis MacNeice eloquently put it: ‘The world is crazier and more of it than we think/ Incorrigibly plural […]’ [2].

Here, we cannot help but be reminded of a remarkably similar phenomenological account, provided in a novel with the very same title: Jean Paul-Sartre’s ‘La Nausée’ (‘The Nausea‘) [3]. In his first novel, the existentialist philosopher Sartre also documents a strict diary-keeping story-teller, who is as baffled by the various meanings of things – and of existence itself – that he begins to experience a continual feeling of nausea, based in his sudden disillusionment with the world around him and his inability to reclaim meaning. After all, Sartre is the same philosopher who wrote that ‘Existence precedes Essence’, or, to put it simply, he realised that it is only given our existence in the world that we can posit any meaning into such a life and that it is, therefore, our duty to decide this for ourselves.

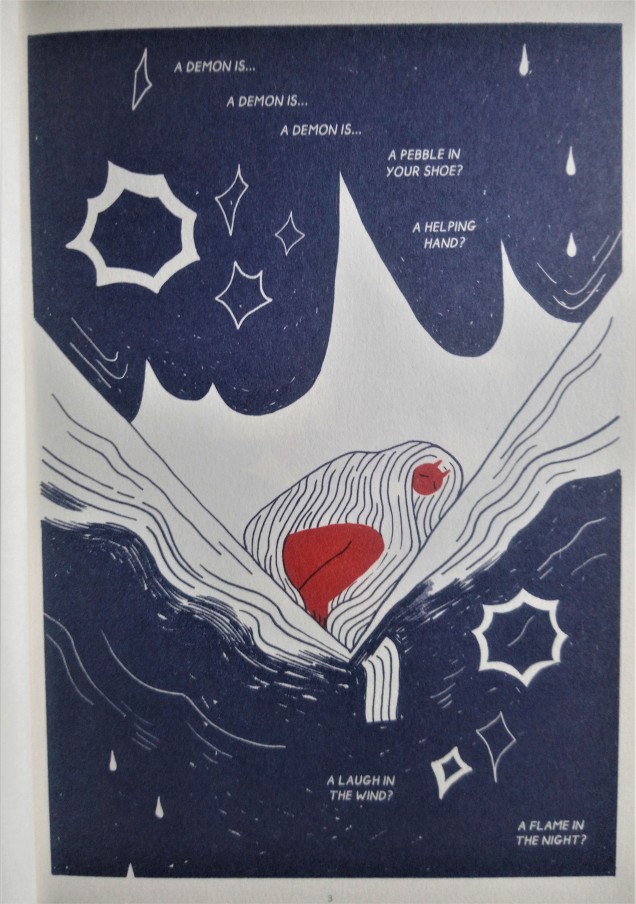

In a way, this is the same mantra with which Murakami encourages those reading his stories to uphold – to add essence to his narrative despite the plurality of meaning. Otherwise, the absurd will simply stay absurd. Towards the end of Sartre’s Nausea, meaning seems to slide and waiver altogether as absurd imagery replaces everything else: in a deep existential angst, the narrator describes centipedes replacing human tongues and facial spots bursting to reveal additional eyes. It has been noted that the core of many existentialist aesthetics (plays, novels, and art produced by the ‘Existentialists’) is a phenomenological one [3]. Perhaps Murakami is also an Existentialist of sorts, his novels and stories are traditionally viewed from the same, rather detached narrator, who observes the absurd happenings within the story with an often frustratingly thoughtful acceptance. This leaves us to simply consider our theories, which will be bound up in our own experience of the world.

In the end, the meaning of the nausea and the phone calls is left open. The only advice offered by the Murakami in the story is this: ‘the problem is which theory you are willing to accept. And what you learn from it’ (p. 196). And I think this a philosophy to be applied to reading any meaning or symbolism into Murakami’s writings: it doesn’t matter what he intended by this image or that metaphor, what matters is what meaning resonates within us; something that we can learn from.

[1] Murakami, Haruki, ‘Nausea 1979’ in Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman (London: Vintage, 2007) pp. 183-197.

[2] MacNeice, Louis, ‘Snow’. Accessed via https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/snow/ on 03/12/18.

[3] Smith, David Woodruff, “Phenomenology”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/phenomenology/>.

[4] Deranty, Jean-Philippe, “Existentialist Aesthetics”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/aesthetics-existentialist/>.